When asked which name comes to mind when you think of Indian independence movement, most Indians will say Bhagat Singh after Mahatma Gandhi and Subhas Chandra Bose. This hero is etched in our minds so deep that we cannot think beyond him when talking of youth movement during our fight for independence.

If Bhagat Singh the socialist revolution of the Indian independence movement whose two daring acts of dramatic violence against the British in India and execution at age 23 were to be alive today he would have been 113 years old. He was born in Lyallpur, western Punjab, now in Pakistan on September 28, 1907.

His place in history

Singh and one of his associates named Shivaram Rajguru shot a 21-year-old British police officer, John Saunders, who eventually died in Lahore, British India, in December 1928. They had mistaken Saunders for the British police superintendent, James Scott, whom they had intended to assassinate.

They wanted to kill Scott because they thought he was responsible for the death of popular Indian nationalist leader Lala Lajpat Rai, as he had ordered a lathi charge in which Rai was injured. Within two weeks of this aid of a heart attack. Chandra Shekhar Azad, another associate of Singh, shot dead an Indian police constable, Chanan Singh, who tried to pursue Singh and Rajguru as they fled.

After being underground he surfaced again in April 1929 and made his presence felt by exploding two improvised bombs inside the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi along with another associate, Batukeshwar Dutt. After which they allowed themselves to be arrested while showering leaflets from the gallery on the legislators below and shouting slogans.

Their arrest and the resultant publicity brought to light his involvement in the John Saunders case. While waiting for trial, Singh joined fellow defendant Jatin Das in a hunger strike, demanding better prison conditions for Indian prisoners gained which garnered much public sympathy for him. Unfortunately, the strike ended with Das’s death from starvation in September 1929. Finally, Singh was convicted and hanged on March 23, 1931, aged 23 in Lahore, Pakistan.

Atheism and Bhagat Singh

Singh was a revolutionary and religion had no place in his life. He started to question religion and their ideologies after witnessing the Hindu–Muslim riots that broke out after Mahatama Gandhi stopped the Non-Cooperation Movement. He questioned how members of these two religious groups, who initially were united in fighting against the might of the British power, could kill each other because of their religious differences.

This was the time when he dropped his religious beliefs, as he realized religion hindered a revolutionary’s struggle for independence. He is known to have studied the works of Bakunin, Lenin, and Trotsky who were all atheist revolutionaries. And even read Soham Swami’s book Common Sense.

There is an interesting account when he was in prison in 1930–31. Singh was approached by Randhir Singh, a Sikh leader and a fellow inmate, who later founded the Akhand Kirtani Jatha to convince Singh of the existence of God. Randhir Singh tried and failed and so berated him by saying, “You are giddy with fame and have developed an ego that is standing like a black curtain between you and God”.

In response, Singh wrote an essay entitled “Why I am an Atheist”. In which he addressed the question of whether he was an atheist due to his vanity. He wrote in support of his own beliefs and said that he used to be a firm believer in God, but he did not believe the myths and beliefs related to religion. But he accepted that religion made death easier, but also went on to say that unproven philosophy is a sign of human weakness.

In this context, he wrote that as regard to the origin of God, he believed that man created God in his imagination when he realised his weaknesses, limitations and shortcomings. Because this is was the way man got the courage to face all the challenges and to meet all dangers that he might encounter in his life and also to control his outbursts in prosperity and affluence. Finally he said the idea of God is helpful to a man in distress.

Towards the end of the essay, he went on to write that his atheism will be tested during his last days as one of his friend’s had told him that he will end up believing and praying to the Almighty. But he said he will never reach that state as he considered it to be an act of degradation and demoralisation. And that if this firm belief is vanity then so be it.

I personally am a big fan of Bhagat Singh’s thought process.

Can ideas be killed?

In the leaflet he and his associate Duttthrew in the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi, he had written that it is easy to kill individuals but that one cannot kill the ideas. Great empires have crumbled, while the ideas survived. How could a person so young have such profound views I wonder.

The slogan ‘Inquilab Zindabad’ which means ‘Long live the revolution’ though written by Maulana Hasrat Mohani in 1921 was popularised by Bhagat Singh in his speeches and writings and has now become a go-to slogan for the youth today, The youth of India still draw and will keep drawing a tremendous amount of inspiration from Bharat Singh.

(The views expressed are the writer’s own)

Smita Singh is a freelance writer who has over 17 years of experience in the field of print media, publishing, and education. Having worked with newspapers like The Times of India (as a freelancer), National Mail, Dainik Bhaskar, and DB Post, she has also worked with Rupa& Co, a book publishing house, and edited over 30 books in all genres.

She has worked with magazines like Discover India and websites called HolidayIQ and Hikezee (now Go Road Trip). She has also written for Swagat (former in-flight magazine of Air India), Gatirang (magazine of MarutiUdyog), India Perspectives (magazine for Ministry of External Affairs) and Haute Wheels (magazine of Honda).

After turning freelance writer she wrote on art and architecture for India Art n Design. She also worked for Princeton Review as a full-time Admissions Editor and then IDP Education Private Limited as an Application Support Consultant. Smita has her own website called bookaholicanonymous.com which supports her love for books and reading!

You can reach her at: [email protected]

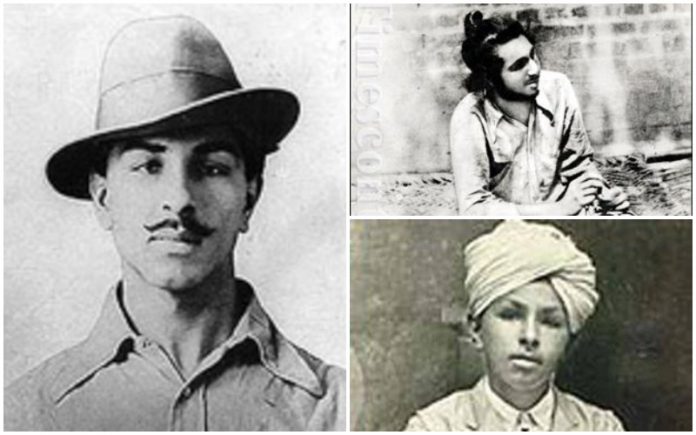

(Collage with images from the net)