This piece is best read with reference to the piece “A story of Tapoi” published in Samachar Just Clickon 24 September. There I had presented a lokakatha version of the story of Tapoi. In the last paragraph, I had hinted that there is a version of this story told in the puranic mould.It is this story that is recited during the worship. It is very likely that this indeed is the story that people know today, not its lokakatha version. Dharmagrantha Store, Cuttack has published it under the title “Tapoi O Khudurukuni Osa (Tapoi and Khudurukuni Osa)”. Here I tell this story and also give some details about the osa.

As I had observed in the earlier piece, the story of Tapoi is more or less the same in both the lokakatha and the puranic versions, except for the ending. There is just one main difference between the two versions in the middle. In the puranic version, the brahmin widow who advised Tapoi’s sisters-in-law not to be indulgent towards the girl and to send her to the forest to tend the family’s goats instead, was a celestial, an apsara, in the guise of a human. She was Tapoi’s co-wife in the celestial world and her name was Lila. She was jealous of her and couldn’t stomach the life she was enjoying in the mortal world.

For some misdemeanour or the other, apsaras were cursed either by gods or sages to be born in the mortal world. After the designated period, the cursed one had to return to her world. Now, Tapoi had been cursed by Indra to spend sixteen years in the mortal world and the story had to restore her to the celestials’ world.Just a few days were left for Tapoi to complete her exile on earth.Chitrasena, her gandharva husband, who had missed her sorely for all these years, pleaded before Indra to allow her to return to him. Indra told him that he must bring back Tapoi the day she completed her sixteenth year on earth. Tapoi had just been married to the virtuous son of the prosperous sadhaba named Biranchi and she was very happy at her in-law’s house. On the eighth day of her wedding, she completed her sixteenth year and the moment that happened, Chitrasen appeared as she was returning home from a ritual worship, accompanied by her relatives and before anyone could make sense of what was happening, he sat her in his floral chariot and flew to the celestial world. As they paid their respects to Indra, Tapoi regained her apsara form and lived happily with Chitrasena.

To return to the six sadhaba women with bloodied noses, who had entered the forest hoping they would be killed soon. In the lokakatha, they were devoured by a huge and hungry tiger. In the puranic version, they were scared when the saw the tiger and fell into a swoon. To cut it short, by Lord Shiva’s grace, their noses were completely healed and became normal. Then they went to their respective parents’ house.

When Tapoi left, her brothers realized that being a divine, she was never really their own. They felt very bad that they had been unfair to their wives and people also blamed them for their treatment of their wives. Then they heard that they were in their parents’ place. Each sadhaba went to his wife’s place and pleaded with her to return. They all did and happiness returned to the family.

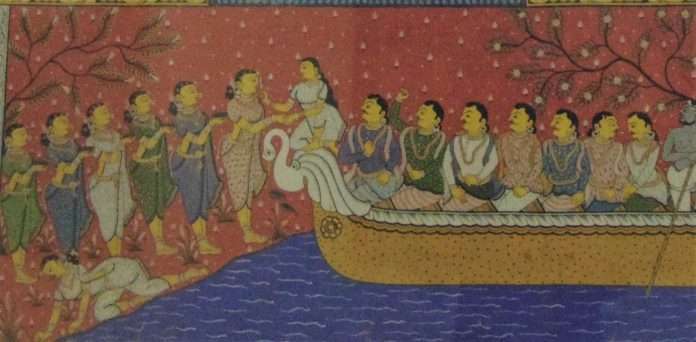

These sadhaba women were the first to observe the osa and worship goddess Mangala for the welfare of the family. On Sundays in the month of Bhadra (also known as Bhadraba), they observed the fast. With coloured rice and other rangoli materials, they drew goddess Mangala and then they drew boats andalso drew Tapoi seated on the deckin one of these.They didn’t mean to express their repentance for the wrong they had done to her; on the contrary, they recalled how she had cut off their noses and laughed and ridiculed her. More likely, it was for fear of her that they drew her. But they didn’t give her the knife. “If we give her a knife, she will cut off our noses again”, they said. Then, in front of the goddess they placed coconuts, bananas, cucumbers and other local fruitsand fried paddy sweetened with jaggery syrup in various forms and offered them to her. We may note that here it was not Tapoi’s worship of Mangala but the sadhaba women’s and Tapoi is part of the of the worship offered to the goddess. She couldn’t be left out because she had become an integral part of the narrative for that particular worship of goddess Mangala.This is not Khudurukuniosa and this osa of the sadhaba women has disappeared from our osa – brata calendar.

Khudurukuniosa is the unmarried girl’s osa for her brothers. It drives fromTapoi’s worship of goddess Mangala. In the puranic version of her story, when she returned to the forest to look for the goat in that dark, rainy evening, she came across a few girls who were worshipping the goddess and joined them. She had nothing to offer to the goddess, barring the handful ofbroken rice that she had with her. The goddess, who bestows prosperity on her worshippers, is worshipped as the goddess who longs for this food of the poorest of the poor. She was so pleased with this humble offering that it became part of the name she has since then: “Khudurukuni”, which is the popular spoken form of “khuda-rankuni”, that is,“the one who longs for broken rice”. Come the month of Bhadra or Bhadraba, as it is called in Odisha, and every Sunday of the month, young unmarried girls observe the ritual fast and worship goddess Mangala for the safety, prosperity and the general well-being of their brothers. These days girls observe the fast for their own well-being as well.

Brahmin girls do not observe this fast. It seems they are not even welcome to the worship. A Bhubaneswar-based brahmin woman told me that when she was a child, her mother had asked her not to go to the puja. The worshippers wouldn’t like her to be there, she had warned her. This is not a caste-based restriction. The brahmin girls are excluded because a brahmin widow was the source of Tapoi’s misery.

But think! If Tapoi hadn’t suffered, would she have become part of our cultural memory? Shewould have lived in luxury for sixteen uneventful years on earth and then joined her celestial spouse. Hers would have been a terribly boring story.So, didn’t the brahmin widow save her story from such a fate? Didn’t she immortalize her?

The linguist Anindita Sahoo told me that she couldn’t observe the osa because she had to go for coaching on Sunday mornings and evenings. A girl who observes the osa is expected to collect flowers in the morning, have her bath and join other girls in “balunka” puja (ignoring details, it is the worship of Lord Shiva in the form of a linga made of seven handfuls of sand or earth, as available) right near the river, pond or well, where she had had her bath. In the evening, she must join the girls in the worship of the goddess during which the story of Khudurukuniosa is recited.With morning and evening tuitions, it was impossible for Anindita to observe the osa. And I am told, hers is by no means an isolated case.

Years ago, this osa was observed in mainly the coastal districts of Odisha on account of its association with the maritime trade of ancient Odisha. Its equivalent, “Bhiajiuntia” is observed by unmarried girls and married women in Western Odishaon the day of Mahastamiduring the Durga Puja. They observe it for the welfare of their brothers alone, not for their family’s or their own. Now because of intra-state migration and consequent cultural interaction,many migrants in the state are observing both Khudurukuniosa and Bhai jiuntia. Isn’t that beautiful?

(The views expressed are the writer’s own)

Prof. B.N.Patnaik

Retd. Professor of Linguistics and English, IIT Kanpur

Email: [email protected]

(Images from the net)