It is undeniable that Odia is not yet the language of modern knowledge in any domain of knowledge: science, technology, law, human sciences, art, etc. It is also undeniable that at least to some extent, this observation would hold good for the other major languages of our country. Then the question arises as to why these languages, almost each of which has a fairly long and rich literary tradition, have not become the languages of modern knowledge, in the sense that, this knowledge is not even disseminated, let alone created, in a sophisticated way in these languages. We try to deal with this question with respect to Odia but we believe that our explanation, although tentative, would not be restricted to this language.

A language satisfies the communicative needs of its users, be they its native or its non-native speakers. Let us use the term “users” for both. It serves our present purpose. Now, if the users of a certain language never felt the need to create knowledge, say, concerning the structure of the sun or the sub-atomic particles or the superconductivity of certain materials, or the neurological structure of the human brain or how machine learning is different from human learning in the case of language, then this language would not have the words needed to talk about these. When they feel the need for this knowledge, they will coin the necessary words. The vocabulary of a language is a reflection of the knowledge of the world of the users of that language, i.e., the world they live in, not the world some others live in. In this sense, no language is potentially less adequate in terms of its expressive power than any other language.

It may be perfectly meaningful to describe some languages as “developed” and some others as “undeveloped”. However, it must be noted that the status of a language in these terms is the consequence of the communicative need of its users and that need itself is a consequence of many societal factors, including historical accidents. Our languages are not “weak” languages; it is just that those among us, who are well-informed about modern knowledge in their respective fields of interest and training, have not chosen to use our languages for the creation and dissemination of this knowledge. It is not due to their being unfond of our language, as some intellectuals and language activists of Odisha say. The reason is that those, who have acquired sophisticated modern knowledge in various knowledge domains through English, simply find it convenient to disseminate that knowledge in English.

Now, for various reasons, mostly sociological, including the lack of patronage, path-breaking knowledge stopped being created in the Sanskrit language centuries ago. As the world evolves, new problems and new challenges arise and people have to deal with them. There arises then the need for a new understanding of the world and for developing new technologies. It is said the telescope was devised to deal with the problem of sea piracy. It was just that Galileo turned it skyward and what he found revolutionized physics. In any case, much creative probing and application happened in some European countries around the fifteenth century. This had happened in India and other ancient civilizations much earlier. In due course, English became the language of new knowledge. I have no idea why it became so, considering that many great scientists from the fifteenth century onwards were non-English.

It is not that the Indians have not contributed to modern knowledge. Those who have made stellar contributions include Srinivasa Ramanujan, C.V. Raman, J.C. Bose, S.N. Bose, Meghnad Shah, P.C. Mahalanobis, P.C. Ray, HarGovindKhurana, Ashoke Sen. There are many, many others. For centuries there had been no interaction between the scientists in India and in the West and once that interaction happened, our scientists were able to participate in the global enterprise in science and contribute to it. The fact is that their contributions are all in the English language.

The great Odia naked-eye astronomer, Samanta-Chandrashekhar, better known as Pathani Samanta, wrote his scientific treatise “Siddhanta Darpana” in the Sanskrit language a little more than a hundred years ago (this great work was published in 1899) because of the lack of the necessary technical terminology and as a consequence, technical discourse, in astronomy in Odia language. He didn’t try to create the necessary vocabulary to write his research in Odia. He was aware of his audience – the scholarly community of astronomers. But the almanacs, used in Odisha, based on his calculations, were never written in Sanskrit. Not specialists but ordinary people use the almanacs. So they have been always written in Odia.

One can’t fault Samanta Chandrashekhar for not making the effort to write his research in Odia and not laying the foundations for the development of scientific discourse in this language. The scientists everywhere write for their scholarly community. Scientific work is not intended to be read by the non-specialists. A work of popular science is. Instead of reading Einstein’s writing on the theory of relativity, a general reader should read Bertrand Russell’s “ABC of Relativity”. Because “SiddhantaDarpana” was written in Sanskrit, PathaniSamanta’s research could reach the community of researchers in astronomy outside Odisha.

The above would account for why our great scientists of modern times, some of whom have been referred to above, have not written their research in their own language or translated their scientific contribution into their language, which would have meant taking time off from their path-breaking work. Scientific research, like any creative work in other fields, is an act of intensity and is intellectually intoxicating. Besides, today, science and technology are global enterprises and the scientific community is a global community. One can share one’s work with other members of this community in a language that the community understands. English, not for some inherent strength of it as a language, but for historical reasons, happens to be this language.

One might argue that English is not the only language that the global scientific community understands, but the fact remains that if one uses a language other than English to present his (her/their) research findings in a standard technical journal, one has to provide at least a summary of it in English as well. Besides, there may be other languages that the scientific community understands, but again for historical reasons, it is English that is most accessible to the Indians. Hence the choice of English here.

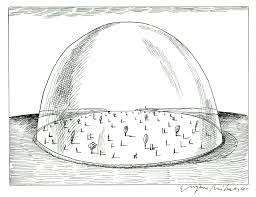

Setting aside practical considerations (which are no doubt very important), such as using them as the medium of technical education at the higher levels, developing language tools in our languages for use by the common people, etc., it is important that our languages have to become carriers of modern knowledge in every domain of knowledge: humanities, human sciences, physical, biological and other sciences and their application (technology). Only then can our society become a truly knowledge society.

In such a society, not everyone, not even most, will create knowledge, but ideally, everyone would understand the meaning of what is being created and its possible consequences on all those life forms that inhabit the world. Enabling our languages to become language of knowledge is not just a value, but an imperative in itself. Contributing to this effort is, in our opinion, a sacred duty of the speakers of a language, who have access to modern knowledge.

(The views expressed are the writer’s own)

Prof. B.N.Patnaik

Retd. Professor of Linguistics and English, IIT Kanpur

Email: [email protected]

(Images from the net)